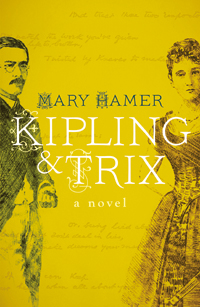

Kipling and Trix - Fact into fiction: how I went about it

People who like Kipling really love him and often know a huge amount, so I knew I was taking on a challenge when I decided to write a novel about his life. How could I keep true to the sense of him that we get from his writing—poems, stories and volumes of letters—while at the same time letting my imagination have play?

My answer was to steep myself in Kipling's world and in the books he left behind before thinking of writing a word of fiction. I read the biographies, returning to the ones by Andrew Lycett and Harry Ricketts. Because I suspected that the Boer War marked a watershed for Kipling I studied it in detail. I called up boxes of letters from archives, chased obscure leads.

I also volunteered to write notes for the Kipling Society website on all the poems in The Five Nations, a collection he published following that war. I read what his friends and some of his enemies had said about him, for I wanted to see him from all angles, not as some kind of hero, though I did come to be moved by his courage and his struggle to keep going in the face of terrible loss.

Already familiar with Bateman’s in Sussex, the Jacobean house Kipling and his wife lived in from 1902, now belonging to the National Trust, I decided to get to know as many other places he’d lived in as I could. In Mumbai I visited the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art, where his father taught and in whose grounds he was born.

Back in England, I squinted through the gate of Lorne Lodge, the House of Desolation in Southsea, where young Ruddy and his sister were so unhappy, and prowled round The Elms, a house Rudyard and his wife Carrie rented in Rottingdean as young parents. I travelled further afield, examining even the door-fittings in The Woolsack, the house Cecil Rhodes refurbished for him outside Cape Town. In Naulakha, the house the Kiplings built in Vermont, I slept in their bedroom.

At times I’ve felt uncomfortably close to a stalker, especially knowing how much Kipling hated being observed. Seek not to question other than/The books I leave behind he wrote. He did write that. But in working on my own book, I think I can say that I have been questioning his writing and the place it came from in him, puzzling too over the strange turn his sister’s writing took.

For it became clear that his sister’s story was quite as fascinating as his own, though information about Trix Kipling was much thinner on the ground: I’ve been lucky to meet with Barbara Fisher, who is writing Trix’s biography. To Barbara and to the book Kipling’s Forgotten Sister by Lorna Lee, I owe a great deal, both of specific information and of leads. Recently I spent a night in Trix’s old home in Edinburgh.

Splicing together the biographies of brother and sister was all my own work and would certainly have been achieved more efficiently if I’d been methodical on starting out. But that’s the fault of the novice: experienced writers of fiction have storyboards and plans. I just kept going back to leaf through the index in the biographies by Andrew Lycett and Lorna Lee.

In the end, though, I had to start writing, jumping off from the facts into making up conversations and letting my characters speak.

From reading letters, Kipling’s own, his wife Carrie’s, Trix’s, and letters by the Kipling parents, Alice and Lockwood, I had a sense of their voices. I had to trust that and plunge in. Occasionally in the novel, when I needed them, I made up letters: from Alice to her sister Georgie and from Rud to Carrie, when he left her and set off on his travels as a young man. Many years later, there really was one day when Carrie got one telegram after another from her husband: I enjoyed working out what might have lain behind that.

At a number of points in Kipling and Trix I draw on individuals for their actual recorded words, words that pointed me and I hope will point readers in particular directions: these are Henry James with his early praise of Carrie, plus his warning to Rud against politics, also Carrie’s own sharp comment on the strains of being married to a writer.

Almost the only characters I made up in order to serve my purpose from time to time were minor ones, such as people who were employed by the Kiplings. Aunt Christiana, a relative I invented for Jack Fleming, Trix’s husband, was an exception. But Trix wouldn’t have been the first young woman to find herself attacked for her truthful voice and I wanted to see what happened when she spoke out.

As for Jack Fleming himself, I fear I may have been harsh, taking my cue too exclusively from the Kiplings. He was unlucky to fall in love with Trix.

I really did want to follow through what actually happened in the course of these lives, to join up the dots, as it were, so that they made emotional sense. It’s my hope that those who know their Kipling will smile as they pick up details that are familiar.

On one single occasion I did take an absolute liberty, when I made the connection between Trix’s breakdown of 1898 and what she saw in the crystal ball, which she did in fact use. Not wanting to spoil it if you haven’t got there yet, I’ll say no more.

But I was quite proud of making that up.

If you have questions about whether any other features are historical rather than imaginary, do email me on:

kiplingandtrix @ gmail . com